Книга: A Different Kind of Freedom

A Different Kind of Freedom

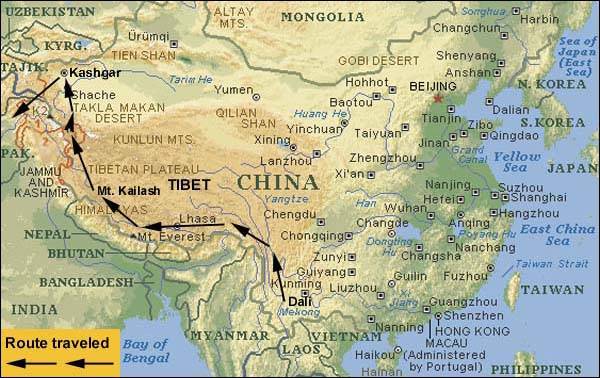

The route starts in southwestern China, in the rural town of Dali, just to west of Kunming, Yunnan. This area forms the eastern terminus of the great Himalayas, the start of the journey. From there it goes northwesterly into the eastern part of Tibet, locally known as Kham. The high forested mountains and valleys of Kham finally give way to the area of central Tibet and the capital city, Lhasa. Leaving Lhasa the road goes toward Mt. Everest and just before reaching the Nepal border a dirt track points the way to the holy Mt. Kailash of Western Tibet. From this most scared pilgrimage site, the main road goes northwesterly through Ali, then across one of the highest most desolate roads in the world, crossing the Askin Chin basin. After descending from this 16,500 foot basin, the Kunlan Shan Mountains are one of the last obstacles before reaching Kashgar in far western China. The Karakoram Highway connects this silk road town with Pakistan and is followed to the final ending point of Gilget, Pakistan. The entire route covers a distance of more than 3,300 miles (5,500 KM).

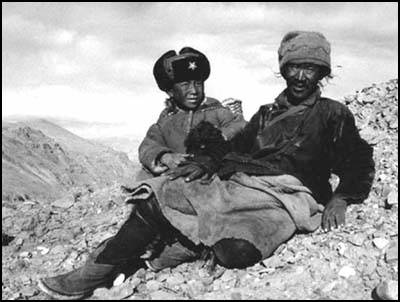

“They lived on old hard, dried raw meat, butter, sour milk and brick tea. They made boots and straps of the wild asses skin, and thread from the tendons of the wild beast. They and their women took care of the tame yaks, the sheep and the goats. Thus their lives passed monotonously, but healthily and actively, from year to year, on dizzy heights, in killing cold and storm and blizzards. They erected votive cairns to the mountain gods, and venerated and feared all the strange spirits that dwelt in the lakes, rivers and mountains. And in the end they died and were borne by their kin to a mountain, where they were left to the wolves and the vultures.”

– My Life As An Explorer, Sven Hedin, the first Westerner to circumambulate Mt. Kailash, 1907

Flying along at 30,000 feet [9100 meters] above the Pacific Ocean, I sat on a China Air flight from Taipei, Taiwan to San Francisco. The Boeing 747 carried me home from a ten-month trip through Asia. At first what had seemed like a haphazard course through most of Asia, in retrospect was a great circuit around the Himalaya traveling through Nepal, India, Thailand, China and Tibet. The 13-hour flight seemed to last for days. While the daylight outside the plane changed to night and back again, I planned what would consume my being and my life for the next two years.

I had a simple idea in mind. I wanted to ride the greatest mountain bike route in the world. A 3300-mile [5500 km] solo ride that would follow the length of the massive Himalaya. It started in southwestern China, in the province of Yunnan, where the Himalaya end near the Chinese-Burmese border. From there I would stay on the north side of the Himalaya and cycle the length of Tibet, finishing on the other end of the great ridge, where Pakistan, China, and Afghanistan all come together. The route would take me to Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, and former home of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, the religious and political leader of Tibet. From Lhasa I would follow one of the centuries-old trade routes out to the most sacred mountain in Asia, Mt. Kailash in Western Tibet. Then the last leg would lead me to Kashgar, the hub of the silk road in Central Asia, on one of the highest, most desolate roads in the world.

When my plane landed in San Francisco, I hopped on the bus down to Palo Alto and walked the seven miles up to where I had been living. Maybe I had been in Asia too long, but somehow walking that last remaining portion of my trip home seemed like the right thing to do. I picked up a pint of Ben amp; Jerry’s Toffee Heath Bar Crunch ice cream en route, a treat impossible to find on the other side of the planet. Sometimes there is no place like the USA! I could not have planned it any better. When I got home my housemates anticipated having Thanksgiving dinner in another hour, they had no idea that I was returning from Asia, I wanted to surprise them all. By American standards we ate a normal Thanksgiving dinner, but compared to where I had been only a couple weeks before we enjoyed a royal feast.

I worked as a consultant in Silicon Valley for the last few years, doing easy jobs and receiving great wages. Before I knew it, I had begun work at another software consulting job. I spent a few hours a day programming UNIX computers, writing software to control large-scale telephone switches for fiber optic long distance telephone networks, then continue with the research for my trip. At four in the afternoon I headed home for a strenuous mountain bike ride and to study spoken Chinese in the evenings. I had picked up a little Chinese and Tibetan on my last trip but I knew I needed a much greater proficiency of both languages. On the trip I had planned I anticipated that I would go for weeks without speaking English. I knew that I must be conversational in Chinese. Every day during my standard San Francisco Bay Area commute I listened to Chinese language tapes, practicing to myself in Chinese “Hello, are you Comrade Chen?” “No, I’m not Comrade Chen.” In the evenings I conversed with an American-born Chinese housemate, each of us jokingly addressing the other as “comrade”.

I love maps. In my living room an enormous map of the world covers an entire wall. I sit and daydream for hours, checking out different places on this map. Maps of Tibet are always difficult to come by. I could not just call up American Automobile Association and ask, “Could you make me up one of those trip-tic things for a trip across Tibet?” I wanted to start down in Dali, Yunnan, China, head through Lhasa, Mt. Kailash, and on to Kashgar. If this was an easy task, everyone would be setting out this ride. After a couple months, I finally tracked down a set of US military maps that cover the entire planet, called Observational Navigation Charts or ONC maps. When I received my copies, I pinned the 6 foot by 8 foot [2 meter by 2.5 meter] section of the ONC maps to the wall adjacent to my world map. I quickly realized that these maps were intended for jet fighter jocks. Over parts of the map covering North India and Western China there were boxes reading “Aircraft Infringing upon Non-Free Flying Territory may be fired on without warning.”

By most every measure, I lived an easy life in California. I had delicious food to eat, a warm place to live, and just about all the material comforts that I could ever want. Twenty-four hours a day, I could go to a supermarket to get as much ice cream as I could eat. I could pick up a phone and have someone deliver a hot pizza right to my house. I truly lived the life of royalty. Somehow in all this luxury, part of the challenge of life disappeared. It seemed to me that the life of hardship that I would face in Tibet would balance out the life of material ease that I had enjoyed in California. I do not think I would have sought out such a demanding journey if my life in the USA had not been so comfortable.

On a roadside billboard, advertising a shopping mall, I have seen a sign that reads, “Over 100 stores, over a million choices.” Sometimes this is one of the problems with the USA, you are inundated by choices, thousands and millions of choices everyday. It seems that most every consumer activity involves far too many decisions. I have often seen people suffer from what I have heard referred to as “Analysis Paralysis.” This common malady can often manifest during any type of shopping activity. On a simple trip to get something to drink at Safeway, an entire aisle of varying types of bottled water bombards you with choices. It seems that when so many choices of virtually identical products overload your brain you become paralyzed by the process of trying to make an intelligent decision. There is something to be said for life in the third world where far more simple choices abound. I am not sure that I always need 72 different types of oatmeal to choose from.

List of equipment, list of things to do, list of lists. I had an unending list of tasks that I needed to do before I took off for China, buying a water filter, tools, building my bike, on and on. As my departure date I chose April 1, 1994. The seasons in Tibet had determined the date. Much later I would learn that there would be many things on this trip that would remain out of my control.

My Dragon Air flight landed in Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province in the People’s Republic of China. This region of Yunnan Province borders both Burma and India. The PRC has a law stating that foreigners cannot possess private vehicles. Whenever I have inquired at Chinese Consulates I have always gotten different answers as to if a bicycle constitutes a private vehicle. I had packed my mountain bike in a small cardboard box. The idea that Chinese custom officials would not let me into the country with a bike worried me. When I pushed my cart up to the customs counter, the official asked me in Chinese what I had. I replied, in Chinese, “This box is my bike and that one has my clothes.” She waved me through without even inspecting my boxes. A feeling of relief calmed my nervous mind. I suddenly realized as I stood out on the street that I did not have any renminbi, Chinese currency. In my anxiousness to get through customs I had completely forgotten to change any money. I asked another American, whom I had met on the plane, to watch my baggage. When I ran back through customs, no one blinked an eye. I changed US$50, and ran back through the customs gate again. So much for my worries of strict Chinese officials.

My first hotel room tempered my immersion into China, it held both a hot shower and a color television. The next morning I woke up to a bouncy 12-hour bus ride to Dali. This marked the beginning of my mountain bike trip-the beginning of a trip from which I was not sure I would ever make it back alive. Dali is a great little town nestled between Erhai Lake the 13,000 foot [3963 meter] peaks of the Cangshan Mountains. It is a backpacker hangout in an area that is mostly inhabited by the Bai and Naxi hill tribes, two of the fifty-three ethnic minority groups in China. I listened to Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead sing “Knocking on Heaven’s Door,” while I relaxed in a small travelers’ cafe. I spent most of the afternoon stuffing myself with tasty treats. I knew that this was one of the last places to enjoy any Western-style food or music for a while.

I had a beautiful day to start, brilliant sunshine and snow-covered mountains surrounded me. Nothing compares to riding a bike in the sun while looking up at snow-capped peaks, that was why I traveled halfway around the world. I knew that the first part of the ride would be straightforward, but I would rapidly cross the border into the part of China restricted from foreigners. This line moved back and forth all the time. During Chinese crackdowns in Tibet, security would be tight in all the Tibetan border areas. For the last few months I had been hearing that things had loosened up in Tibet. That news sounded good to me. Most of my entire trip ran through an area totally closed to foreigners.

My first Chinese checkpoint came quickly. A large red and white turnpike blocked the road, and a few Chinese policemen talked among themselves in front of the guardpost. I decided to keep pedaling. I approached the turnpike and pushed my bike under it. With a quick glance back, I saw a guard holding an automatic weapon across his chest. Things seemed pretty cool, no one yelling at me, just a “nihao” (‘hello’ in Chinese). I had been baked by the hot sun for most of the day. I needed drinking water. I took my chances and stopped to chat with the checkpoint guards. They were a group of young guys from Beijing, with one gun and one hat between all of them. They would hand the gun and hat to the next guy whenever the soldier on duty wanted a break. Like most policemen stationed in Western China, the work bored these guys out of their skulls. My presence meant entertainment for them. While they asked me a few questions about where I came from, I heard a video game somewhere in the back room. After investigation, I found a group of guards playing a game from Hong Kong, called “Contra.” In this brutal game Rambo-style heroes get to fight head to head against the video images of Nicaraguan Sandinista forces. Sometimes I am so far from the USA, sometimes I never leave.

The hardest part of a long uphill on a bike is not knowing how much more remains. The great thing about cycling in a Tibetan area is that prayer flags always wave in the wind marking the top of passes. I climbed my first real pass, 10,500 feet [3200 meters], an entire day of cycling uphill. When I saw the small colored flags that release prayers as they blow in the wind, I knew I had returned to Tibet! The Tibetan prayer flags or “wind-horses” came from the pre-Buddhist practices of Bonpo, the folk religion of Tibet. Each of the flags is imprinted with images and prayers meant to purify the wind and please the gods. This pass signaled what would be the first of countless days of climbing. By the end of the trip I had succeeded in climbing 160,000 vertical feet [48,700 meters] of uphill, almost six times the height of Mt. Everest. This marked the beginning of the climb into what makes up the eastern edge of the Himalaya. Some of the great rivers of Asia flowed through the valleys of this area. The Mekong finds it way south to Vietnam, the Yangtze east to Shanghai, and the Brahmaputra cuts southwest into India.

Zhongdian sits on the southwestern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. The town consists of a mix of ugly Communist Chinese concrete buildings and old adobe Tibetan houses. Since it is the county seat, there are a large number of Chinese government buildings and Chinese workers in the town. I have often wondered who could design such hideous concrete cube-shaped buildings, which seem to set the architectural standard for the PRC. Up until just six months earlier this area had never officially been open to foreigners.

After my arrival in town, I learned that the one and only backpacker hangout was a little place called the “Lhasa Cafe,” which was run by a young Naxi and Tibetan woman named Lama. A wonderfully energetic and intelligent woman. By herself, she created and managed this hip cafe. Lama and I quickly became friends. She wanted to learn more English and I wanted to learn more Chinese. We both had roughly the same level of language skills, respectively. During one of our many conversations, I mentioned the English word “capitalist,” which she did not understand. I looked up the word in my Chinese/English dictionary and showed the characters to Lama. When she spotted the Chinese definition she reacted rather adversely to the word and the concept. I instantly realized that this was the result of years of Chinese propaganda. When I asked Lama if she thought she was a “capitalist,” she flatly refused that she had anything to do with being a “capitalist.” I asked her a bit about how she actually ran her business. She told me that she rented the building from the government bus depot, for about 300 yuan (US$60) a month. She also paid both her mother and another woman to help with the cooking. I asked her what would happen if she could not pay the monthly building rent, and she replied, “I would be kicked out.” This all sounded to me to be a purely capitalistic enterprise, but Lama did not want to be identified as being a “capitalist.” After a lengthy discussion, Lama started to understand the true meaning of capitalism. Since Dung Xiaoping’s economic reforms of the 1980’s, China has been in a rather strange state. Officially it is a Marxist Communist country, but in certain areas limited capitalist enterprises are allowed to operate.

Another result of the changes in China was the disco operating next to the Lhasa Cafe. I had seen large numbers of discos in the bigger towns and cities all over China. I had never actually ventured inside of one of these discos before, but I had heard plenty of stories from other foreigners who had lived in China. Lama told me that she went over to the disco every couple nights when they played the “BananaRama” music video. I think I disappointed her a little when I informed her that I had never heard of “BananaRama.” So, when her friend came running over to announce that the “BananaRama” video was about to go on, she invited me to dance with her. One of the few things that I knew about Chinese discos is that most of the time women dance with women and men dance with men.

The entire room glowed red and blue dimly from the overhead lights. Booths with tables where couples were seated in secluded darkness surrounded a central dance area with the requisite mirrored ball and flashing lights. Up at the front of the room sat a small stage with a keyboard, drum kit and microphone stand. Dancing and singing excited Lama. BananaRama appeared to be an Australian pop music group mostly composed of dancers. The synthetic drum machine beat started up and a few people shuffled out on to the dance floor. I stayed on the side for a bit, to just watch. My body perspired with nervousness. I was not sure of what to expect or what Lama expected of me. After the first song, I started to relax and Lama walked over to fetch me. Once I got out on the floor and moved around, I grew more comfortable. As I danced in a Chinese disco on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau, I contemplated the strangeness of this entire event. The bizarre mix of East and West reminded me of stories from Pico Iyer’s Video Nights in Kathmandu.

Being early in the season, the high passes just started to clear enough to allow jeeps through. I had spent the night at the last town before climbing the pass that separated me from the Mekong River valley. I watched for jeeps and trucks coming from the other direction since the day before, but I saw nothing to indicate that the road had completely opened. Many people around town warned me that the pass remained closed, and it would not be possible to cross it on a bike. When I inquired more, they informed me that snow 3-5 feet [1-2 meters] deep extended for 15 miles and blocked the road. I found this difficult to believe. Some folks told me that I would freeze to death. They insisted that I should just wait another week or two until the snow melted more. I did not want to wait. Soon after returning from my first trip to Tibet I purchased the best sleeping bag I could find. I had spent too many winter nights freezing in an old-worn sleeping bag on my first trip to Mt. Kailash in Western Tibet. Each night I would wear everything I had. I wrapped my towel around my neck, put the bottom of my sleeping bag into my backpack and still I would only be able to sleep until 2 or 3 A.M., after that it would be too cold to continue sleeping. With the temperature dropping down to -5F in the worst part of the night, my old sleeping bag was incapable of keeping me warm without a tent or a proper sleeping mat. I would just lay there, turn my face away from the icy wind and wait until sunrise. One morning I had gone to fetch water from the river, to cook up something warm to drink. By the time I returned to my camp and got the stove lit, my pot of water had already frozen over. This time I carried a toasty sleeping bag and a tiny one-person tent. At least I would stay warm even when the temperature dropped below 0F.

The first day I managed to climb 4,600 feet [1400 meters], through patchy snow, nothing too difficult. I knew I was high enough to finish the climb the next day but not so high that I suffer from the cold during the night. At about 3 A.M. the low-rumble of a convoy of trucks slowly working their way down from the top of the pass woke me up. This was a good sign, it must have become passable enough for the trucks to get through. The next morning I started climbing again, little by little more snow appeared on the sides of the road. When I got near the top of the pass, I could see out onto an immense snow-covered plateau. The pure white snow blanketed my entire surroundings. The combination of sun and snow blinded me, I had to keep my sunglasses on to shield me eyes. I quickly realized why everyone had told me that the snow would extend for 15 miles, the road crossed a double pass. I had reached the top of the first pass but it would be another 15 miles onto the even higher second pass. I rode through 15 miles of mud and snow, not that bad, just messy. As I climbed the last bit before the 14,000 foot [4268 meter] pass, I spotted a group of Chinese Army soldiers walking on the side of the road. Their truck had broken down earlier. They decided to try and walk until they could find another ride. Near the top, the mud covered trucks and jeeps lined up in the slushy snow. They had dug ruts two feet [0.75 meter] deep in the snow, nobody could move, someone on the uphill side had become stuck. After a quick rest break, I hauled my bike through the snow and around the immobile mass of trucks. The only thing better than cycling under the sun in the mountains is blasting downhill in the mountains. I slid through the mud and ice, around the turns, with dirt spitting up into my eyes from the front tire. I reveled in a few hours of unending downhill that tired me almost as much as the uphill.

Chinese officials in Zhongdian reported to me that the town of Deqing was now officially open to foreigners. The more places that are officially open the better I can eat and the easier my trip becomes. I quickly found a room in the Deqing government hotel. This place functioned mostly as a truck stop for the drivers that hauled tons of timber out of Eastern Tibet and northwestern Yunnan province. Chinese government hotels always look the same, large concrete buildings a couple stories high, with one or two attendants who live in a bored stupor and do not give a crap if you stay in the hotel or not. Most would actually rather have you not spend the night, so they would not be bothered with straightening the bed covers out in the morning. Changing the sheets was out of the question.

I hauled my bike up the steps, locked it to the metal frame of the bed and headed out to find any other Westerners in town. A quick search turned up a group of four young German backpack travelers. They had stayed in town for a few days and had no problems with the police. I delighted in hearing this report. My immediate task became eating and stocking up on supplies. I shared a hotel room with a young Japanese traveler. We had met on the road a couple days earlier. He looked Chinese and dressed in Chinese Army clothes, so he did not have any worries about the police catching him. A few days of resting sounded enticing to me, but it got cut a little short. My Japanese friend, Toshiba, went to the local Public Security Bureau to inquire about getting his visa extended. The head policeman curtly told him that he could not get his Chinese visa extended and by the way this town was closed to foreigners. Toshiba relayed this story to me back in our hotel room. I decided to head out for a bite to eat before I packed up to leave in the morning.

The Germans always ate at a small little family shop just across the street from the expensive hotel where they stayed. I dropped in to reiterate the story of the PSB policeman, when a large Chinese man holding a red German passport turned around and said in English, “I'm sorry, this type of visa not valid in town of Deqing.” One of the Germans replied with, “But we were told in Beijing, that Deqing was now open…” At this point I realized that I still possessed my passport. I stood up and carefully walked out of the cafe. A couple minutes later I returned to the hotel. I started to frantically look for the hotel attendant with little success. In Chinese hotels only the hotel attendants possess the room keys. A key is never given to the guest. I found a cleaning woman who informed me the attendant had gone out for lunch. I needed to get out of town NOW, not in a couple hours after the police rounded everyone up. After a bit of searching, I spotted a window that we had left open on the other side of the room. It was too high and small to climb in through. I managed to drop my belt down through the upper window to pull the latch open on the lower window. I quickly climbed in through the larger lower window. I jammed everything back into my packs and pushed my bike down the stairs. The town of Deqing covers the side of a mountain. From Deqing only one road continues on to the Tibetan border. To get there I would have to ride back past the cafe where the Germans ate their lunch with the police, a place that I could not afford to return to. I spotted a steep goat trail that zigzagged its way up the hillside to the upper road. With great effort I carried my bike up the goat trail three feet [1 meter] at a time. As soon as I reached the road I sped down the hill, through the main intersection, and out of town. Two hundred yards passed town, Toshiba stood at the edge of the road with his pack on his back. Lhasa was the destination that both of us had in mind. We both knew that the time to move on had come.

Since the Chinese invaded Tibet in 1959, they have created what is called the Tibet Autonomous Region. They have also taken large parts of the border areas of Tibet and have moved them into the surrounding Chinese provinces, effectively reducing the size of Tibet proper. So far, I had ridden in the Deqing Tibet Autonomous Region in Yunnan province, not “officially” in Tibet. As I got closer to the borders of Xizang, as the Chinese call Tibet, I knew that I would have to become more skillful about dealing with the police. I approached the town of Yanjing. I knew that a turnpike blocked the road some place in town but I did not know if the police would be on the lookout for foreigners. I spotted Yanjing up ahead, a small town in the valley between two massive 18,000-foot [5487 meter] ice covered peaks. The afternoon sun shone high overhead. I thought it would be wise to wait until dark in order to facilitate passing through town. Waiting, waiting, waiting, I spent a lot of time on this trip waiting. The worst times always came while waiting for the sun to go down, or waiting for the sun to come up, so I could sneak pass a police checkpoint. The waiting without knowing if my trip was going to be over or if I would be turned back created one of the hardest parts of the trip.

Only a couple of roads cross the region of Tibet. Two of the main routes through Eastern Tibet come together in Markam. Markam is one of the old-time trading posts where the Tibetans from Kham would come together to meet and trade with people who brought goods in from China. It is on the main road that goes on to Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. Markam lies inside the Tibet Autonomous Region, TAR. This represented my first police checkpoint in Tibet. A former Lhasa policeman informed me that foreigners could freely pass through Markam, he assured me that the security police would not be interested in me. For most of the last six months I had heard mixed stories from other travelers. I did not have a choice. I had to stop in the town either way. I was tired and running low on food, and Markam would be the last place to resupply for a while. The sun sat low in the sky, descending toward the horizon. I decided to buy my food and leave in the morning. I had to take the chance.

A Tibetan man, from the truck-stop hotel, called to me in the street, “I have a room for you in my guesthouse.” I figured that maybe he would not turn me into the police as quickly as a Chinese man would, since there is always a bit of animosity between the Tibetans and the Chinese. I was too weak and the stairs too steep to carry my loaded bike up to the room. I unpacked a few things to lighten the load, but still I struggled while hauling my bike up the steep stairs to my room. I immediately headed out to look for a meal and food supplies. Since China is a Communist country, almost every shop is a government store. Most look like a bomb had blown up inside. Glass cabinets line the walls, filled with items that look to be one hundred years old, covered with dust and in some sort of totally random order. I found some jarred fruit sitting next to crescent wrenches. The fruit looked good, but I skipped the foot-and-a-half-long crescent wrench. The only way to find anything in a town like Markam is to inspect every store. After a couple hours of searching, I found packs of dried fish, dried fruit, ramen noodles, and cookies- everything that I needed.

Tibetans call the eastern part of Tibet, Kham. The people that live there are referred to as Khampas. The Khampas are the toughest of the lot. All the men wear their long black hair braided with a 2-inch-thick bundle of thick red strings, wrapped up around their heads. The classic image of a Khampa man shows him with a bottle of chang, local barley beer, in one hand, a foot-long [30 cm long] knife on his belt and an entire leg of yak meat in the other hand. If motorcycles were readily available throughout Tibet then Khampas would be riding Harleys.

Dirt roads run through town covered in mud puddles and horse crap. Most times these small towns remain far enough away from the law that whatever the local police say goes. Huge timbers about eight-feet [2.5 meters] long and two-feet [0.75 meters] in diameter filled the courtyard behind the truck-stop hotel. Piles of logs sat stacked six high. It seemed that someone needed these trees moved to the other side of the courtyard. Since no one owned a crane in town, the hotel owner called the local gang of thugs. The leader was a small tough guy, wearing a calf-length denim coat. He carried a small silver pistol on his belt. Chinese law says that citizens are not permitted to carry weapons, this guy was an exception and I did not want to know why. He sent his crew out to relocate all the logs to the other side of the courtyard, and then ordered up a meal. The cook said something about being out of food, so then the gang leader drew his gun in a half-joking, half-serious manner and said, “I think you can find some food for me.” With that I called it an early night and went back to my room to do a bit of writing and packing. I could not afford to have a rest day in Markam. I knew word would spread quickly that a foreigner had arrived in town.

As my body grew ready for sleep I heard a knock at my hotel room door. Two Tibetan men wearing clean Western style clothing entered the room. They said a friendly “ni hao”, while they sat themselves on the empty beds in my room. They both asked me the standard questions, “What country are you from?”, “Where are you coming from?”, “Where are you going?”. My nervous mind wondered exactly what these guys were doing in my room? Neither of them carried any baggage. Finally one of them told me that they both worked as policemen. He reiterated, “Do you understand? We are both police.” This definitely worried me, why were two police in my room? I carefully answered each question that they asked. As the discussion continued they did not seem concerned with my travel plans. When they finally explained to me that they needed to spend the night in Markam in order to catch an early morning bus, my body relaxed with relief.

A slow but continual climb filled most of the day as I made my way to the top of a 14,200-foot [4329 meter] pass after Markam. Afterward I cashed in on my reward, a 27-mile downhill that brought me back to the banks of the mighty Mekong River. In the course of a couple hours I transitioned from ice and snow at the top of the pass, to basking in the warm sunshine at the banks of the Mekong. Then I crossed the river to a small broken-down shack for a warm meal of rice and vegetables. The Chinese army guys I had seen walking on the road a week before had finally caught up to me. They had been hitchhiking, trying to get to Lhasa, but their trucks would always break down. I ended up leapfrogging them for a couple weeks. It became apparent that travel through this land created difficulties whether on bicycle or truck.

I crossed another pass and still one more pass stood at 16,500 feet [5030 meters]. The highest one I had crossed so far. The lack of oxygen crippled me. I crept along slowly on my bike. At this altitude my legs could move much faster than my lungs could take in oxygen, so I had to learn how to slow down everything I did. By the time I reached the top, a sudden snowstorm had pushed in from the other side of the ridge. I had to move on to get down below the howling winds and blowing snow of the storm. I would freeze if I stayed up this high in a storm. With snow blowing in my eyes making it impossible to see, I put my sunglasses on to give me some kind of protection from the winds and the snow. I stopped to take a picture of a couple of yaks walking across the frozen snow-covered river beside the road. By the time I returned to my bike, the snow had piled up inside my open pack, reminding me that I could not spend much time hanging about. Gravity did its work creating a speedy descent for me. I only stopped occasionally to thaw out my frozen fingers and clear the ice off my sunglasses. A few hours later I enjoyed the warm sunshine at the riverside while I ate a few sweet tasting oranges that I had carried from Markam.

Over the course of the previous couple days, I had been hearing rumors about other Westerners also riding mountain bikes to Lhasa. When I stopped and talked to the road construction workers, they would ask me if I was riding with the other foreigners whom they had seen. When I inquired, I heard that they rode from two days to ten days ahead of me. Every now and then I would spot some tracks on the road that looked to have come from another mountain bike. Once I knew that someone else might be out there making the same trip that I was attempting, everything seemed different. I wondered if there was someone else crazy enough to attempt this same journey. The idea of meeting other Western cyclists intrigued me, but I also felt hesitant to give up the comfort of solo travel.

I had heard that Zogong was a safe place to stop for a rest, no problems with the police. It appeared to be a town of a few thousand people, which meant I could eat well and resupply. By the time I arrived in town, my stomach ached from the lack of food. The day’s riding had worn me down to the bone. I stopped at the first place that looked like it served a reasonable meal of rice, noodles or vegetables. Peering in through the window I spotted a couple of cooked chickens and a few bowls overflowing with fresh vegetables. Once I got off my bike, half the kids in town decided that I was going to be their entertainment for the afternoon. Whether I was waiting for my food to be cooked or eating, I was without a doubt the most popular attraction in town. Certainly other foreigners had visited the town before but most likely not more than a dozen or so a year, with few ever spending more than a couple minutes.

Later in the evening I noticed a black chalkboard sign advertising a video at 7 P.M. It was just outside a small room containing a VCR and a color TV with a few beat up wooden benches for people to sit on, a third world movie theater. It sounded good to me. I could use a little brain-dead entertainment. It turned out to be some kind of shoot’em up blow’em up movie, where a motorcycle gang tried to assassinate a US Supreme Court justice- an American movie that had been copied a few dozen times and dubbed into Chinese played on the VCR with the volume turned up to “11”. The film tried to imitate a Schwarzenegger/Rambo-style movie, but failed. The audience consisted of mostly young Tibetan men and a few Chinese guys. During the middle of the movie a young man asked me if the images came from my country. I answered with a reluctant “yes”, not taking the time to explain that this film did not actually portray normal life in the USA. It embarrassed me to have any kind of association with what I saw in the video. When the movie ended, I walked out to the street. I looked up to see the jagged peaks that I had just descended from, silhouetted in front of the round disk of a full moon. This was Tibet, land of extremes.

This trip was about extremes, about extremes of thought, extremes of feelings, extremes of physical effort and extremes of the environment around me. One day I would be baking in the heat of the sun, the next day snow would be freezing in my beard. One day I would be happy as can be, on top of the world, the next I would be scared, depressed and wondering why I was doing the trip. One day I would be strong as can be and climb the mountain passes as if nothing could ever get in my way. The next I was weak, slow, and I would fall asleep lying in the dirt on the side of the road.

Bamda is a insignificant truck-stop at the intersection of the main road to Lhasa and the road coming down from Northeastern Tibet. I moved slowly that day. Most of the night before I had been up vomiting onto the frozen ground just outside my tent. I could use a decent meal and a bed. When I pulled up, a young Tibetan boy said something about another Westerner in the hotel. Three weeks had passed since I started riding. I had not spoken English in a while. I was anxious to talk with another Westerner. Andrew had started out on this trip three and half years earlier. He had given himself five years to cycle around the world. From his home, Jasper Alberta, he had ridden down to Central America and South America. We spent the evening chatting about cycling and computers. We both set out the following morning on the road toward Lhasa. It was a different experience to ride with someone. Experiences were influenced by and filtered through someone else’s consciousness. It was no longer just me moving through the world. When I spent my days alone I didn’t have someone to reflect ideas and thoughts off of. Just my own observations and my own ideas filled my mind.

I had heard a warning earlier in the journey that the toughest checkpoint between Markam and Lhasa blocked the road just after Bamda. The former Lhasa policeman said that after the famous “72-Bends,” a descent of seventy-two switchbacks, there would be a tunnel through solid rock guarded by a Chinese soldier with a large gun. He said that at this place most foreigners who were headed toward Lhasa were turned back. After the exhilarating two-hour descent down to the river, Andrew and I spotted the guard’s living quarters just before a bridge that crossed the water where the road continued into a tunnel through solid beige colored rock. The river ran far too wide and deep to get across. We both knew that the bridge represented the only way across.

We decided to take our chances, and just try to ride across the bridge. Another building blocked our view of the guard post. Not until we were right on top of the guard did he spot us. About ten feet [3 meters] before the guard post we came into his line of sight. It was all just like I had been told, a soldier with a big gun guarded the bridge with a tunnel that went into solid rock. A heavy belt of extra bullets and other assorted weaponry hung around his thin waist. He held an solid black automatic weapon across his chest. By this point in the trip I possessed reasonable comprehension of Chinese. When the guard yelled, “ni qu nar?” (where are you going?) I knew exactly what he said. I just chose to ignore him. I waved my hand to indicate that we planned to head straight ahead, and kept on riding. He yelled again, “ni qu nar?” We rode on. Thoughts of bullets in the back of my skull raced through my mind. In another fifteen seconds we rode into the tunnel on the far side of the bridge. My mind moved to thoughts of an army jeep coming after us. I listened for the sounds of a jeep engine and kept pedaling hard. Nothing, no trucks, no jeeps, no gun shots, nothing, no one followed us. I kept riding at a strong pace. After another two hours passed I knew that they had no intention of chasing after us. During the next few hours we climbed up a small rocky canyon, regaining the altitude that we lost during the speedy ride down the “72-Bends.”

As part of my research for the trip, I compiled a list of all the main towns on my route. Next to each town I wrote notes as to if the police were rumored to be difficult or not, the remaining mileage to Lhasa or Kashgar, the availability of food. For Eastern Tibet most of my information had come from a friend who had walked the entire length of road from Southwestern China to Lhasa and then down to Kathmandu, Nepal. I had met Robert in the popular Yak Hotel of Lhasa in 1992. He was in the middle of a walking trip across Asia. A few years before, he had spent two and a half years walking from the southern tip of South America to Texas. He lived two and a half years of waking up every morning and walking all day long, then going to sleep and waking up the next day to push on northward. When I met him, I was headed to Kathmandu on a mountain bike and he was headed there on foot. We had a bit of an informal race to Kathmandu. He won, I never said I cycled quickly.

Robert had told me that problems may arise if I spent too much time in the next couple towns. All of these towns only have one main street. I would roll into town, buy some food, and whatever else I needed. Then I would push on as fast as possible. I knew that it would take an hour or so before the police got word of my presence. As long as I kept moving on, things went well.

Andrew had been on the road a long time by the time I met him. I could tell from the way he interacted with the local people that the traveling had worn him down. He was mentally tired of being hassled, and tired of being in a place where he did not always understand what was going on around him. Not speaking Chinese or Tibetan made things even more difficult for him.

Andrew and I had descended from a 14,250-foot [4344 meter] pass to the town of Rawu which sat at the edge of an enormous half frozen lake. On the far side of the lake rose mighty 19,000- and 20,000-foot [5792 and 6097 meter] peaks covered with glaciers and snow fields. Small wooden homes with flagpoles thirty feet [10 meters] high flying prayer flags dotted the fields before us. We both stopped on the side of the road to take in the beauty of this place. When I heard some words in English yelled in my direction, I looked up to see a group of well-dressed Tibetans sitting off to the side of the dusty road. I rolled my bike over to them and exchanged a few words. This Tibetan family had lived in refugee camps in South India for years. The father was a well-educated man who spoke English with an Indian accent. They were some of the few Tibetans who acquired special permission from the Chinese government to enter Tibet legally and visit the family that they had left behind. Decades before, they had fled the invading Chinese army, crossing the Himalaya on foot to settle in refugee camps in India. The entire family was proud of their daughter who had been selected for the special group of 1500 Tibetans that the US Congress had recently allowed to enter the USA as political refugees. She had just moved to New Mexico a few months before. With her clean blue jeans and purple and pink LA Gear jogging shoes, this young Tibetan woman stood out almost as much as I did. The tiredness and hunger wore thin on Andrew. When he yelled that he wanted to head into town I bid the friendly family farewell.

We rolled into town, a small bar stood on one side of the road with saddled horses tied to the hitching post out front and a truck-stop hotel sat on the adjacent side. Word rapidly spread that “inji” (Tibetan for English people) had arrived in town. A group of ten or fifteen dirty kids encircled us. Short pieces of string held their shoes on, only a couple possessed the luxury of real shoelaces. To them we must have looked like creatures from outer space. They carefully checked out our bikes, and our gear, they wanting to press every button and flip every lever. I quickly tracked down the hotel attendant and found us a room in the corner of the courtyard. We ducked our heads under the ever-present low door frame and unpacked a few things. I washed some of the only clothing that I was not already wearing, two pairs of socks. On my way back to the room two older Tibetan men greeted me, I replied with a friendly “Tashi Delag” (Tibetan for “Hello”). We chatted for a bit. When I did not know the correct Tibetan word I would fill in a Chinese word, a little confusing, but everyone seemed to understand. The conversation soon turned to politics, in particular the Chinese oppression in Tibet. Even though I could not understand every word that was uttered, they made it very clear that some major problems existed. The Chinese police often injured or killed Tibetans. My heart went out to these two Tibetan men. I had heard the same stories so many times before, and knew that it would not be the last time because I was headed toward Lhasa and the political and religious oppression is always the worst in the capital. I have never really understood all of my attraction to Tibet and her people, but I do know that much of it has to do with how the Tibetan people deal with adversity in their lives.

When I started to walk back into the hotel room, my two new Tibetan friends followed. They showed some curiosity about the bikes, and started to inspect them. When Andrew spotted these guys in the room he became upset. He yelled, “Get out of the room,” and informed me that if I wanted to talk to the locals not to bring them back into the room. At that moment I knew that I could not continue the rest of my journey with Andrew. We had ridden together for two days. It had been fun talking and riding with him, but he did not share the same vision that I had when it came to interacting with Tibetan people. I certainly had my times when I got fed up with people trying to rip me off and people hassling me, but the important thing was that I had a lot of times laughing and joking with snotty-nosed kids and sharing meals with old nomad women. I also had some language skills that helped me to create these wonderful experiences.

Not until I returned from my first trip to Tibet did I start to truly understand the European takeover of North America. The situation that Native Americans faced when the Europeans started to arrive in North America is extremely similar to the situation that Tibetans currently face with the Chinese. It is one thing to read about genocide as a disinterested high school student, but it is completely different to live in an environment in which the culture and people are being actively destroyed around you. During the 1800s the American government encouraged new European settlers to move farther and farther west offering ownership of land previously inhabited by Native American Indians. Over the course of a relatively short period of time, the Indians were herded on to smaller and smaller remnants of their original lands. Today the Chinese government is executing the exact same plan in China and Tibet, a policy of population transfer, as the Dalai Lama refers to it. Xizang Province is the Wild West of China. It is a land of economic opportunities, harsh environments and hostile natives.

Andrew and I had been eating dinner in the small restaurant in the front of the courtyard. While we waited for dinner I talked with the couple who ran the place. When the big round fellow with the gun sat down next to us, I shut up quickly. He demanded “pass! pass!”, my language skills quickly faded and I pretended to not understand his single spoke word of English. I just replied with “bu zhidao,” (Chinese for ‘I do not understand’). His one word of English came out of his mouth in an intelligible fashion. I just did not want to hand over my passport. The policeman did not seem like a particularly hostile man, but I just could not risk someone confiscating my passport. After about fifteen minutes of him asking and me replying with, “I do not understand,” he walked out. He had had enough of this pointless and idiotic conversation. When he left everyone relayed to me that he was the “Big Policeman,” I remained a bit nervous about the whole encounter throughout the evening.

We both would have liked to rest up in beautiful Rawu, but we knew that we could not risk another run in with the police. I awoke to the sound of rain hitting the metal roof of our dingy room. We slowly rode out of town in a cold mix of rain and snow at dawn. It sure would have been a treat to just lie in bed for the morning. An hour down the road, I told Andrew that I wanted to finish the ride to Lhasa by myself, he understood somewhat but I knew that loneliness tugged at his heart. Five months had passed since he had anyone to ride with. He rode on alone, while I sat by the lake for a few hours. I watched the misty clouds break up and the sun shine down on the pristine lake shoreline.

I always tried to have an idea of what might lie ahead, for at least the next few days. From Rawu things looked wonderful. The road followed the river for the next 150 miles. My altimeter read 12,500 feet [3810 meters] above sea level and I knew that I would drop all the way down to 6,500 feet [1981 meters] in the town of Tangmai. I had not descended that low since the beginning of the trip.

For fifty miles I rode past spectacular ice-covered jaggy peaks that my map indicated rose over 19,000 feet [5792 meters] high. The maps also showed that the remote Assam tribal region of Northeast India lay just on the other side of these mountains. In Rawu I had resided in an alpine region. At one point during the day I watched the rapid change in the surrounding vegetation and found myself in a temperate region. By the end of the day I was happy and hungry. When I saw two Chinese army soldiers standing on the road in front of their camp, I asked them where I could buy some food. They directed me to their army camp. Everyone I asked reiterated that the camp possessed plenty of food but no one could pinpoint a time or place where I could find it. Finally, a soldier took me to the commanding officer. He was obviously unsure about my presence in his camp but my bicycle journey impressed him. He arranged for me to eat in the mess hall when all of the soldiers ate but he made it clear that I could not spend the night. I had an hour before dinner so I decided to just hang out in the center of the compound where all the men played Ping-Pong and basketball. Without much of a wait one of the soldiers asked me to join him in a game of Ping-Pong on the only table. Like most all Chinese soldiers in Tibet boredom filled these guys’ lives. Most of them were from Beijing or Shanghai, and had attended some of the better schools in China. They considered being stationed in Tibet something like being sent to Siberia. Most of them also thought that Tibetan people were not much smarter than dogs or monkeys. My ability to speak some Chinese pleased the soldiers. They wanted to know everything about America. They all had seen Michael Jordan perform his extraordinary basketball skills on TV. I disappointed them when I informed them that I could not play basketball. After a couple of games against my first Ping-Pong opponent, they realized that I could play a half decent game. Everyone wanted to play against me to try to beat the American at Ping-Pong. I enjoyed playing and joking with these guys. When the call for dinner came, one of the officers directed me to the back to the kitchen. The commander allowed me to eat in the back with the kitchen staff and the officer that was assigned to watch over me. They fed me well, rice, chicken, pork and vegetables. By the time I walked out of the kitchen my belly was totally stuffed with wonderful Chinese food.

At the lowest point on this section of the road lies Tangmai-a place covered with dense tropical jungle. This was not the Tibet that I knew. Monkeys filled the trees and smashed snakes dotted the road. I stopped in the only place to eat in Tangmai. When I sat down at the table to wait for my food, visions of India came back to me, the heat, the sweat, the hoards of flies everywhere. From Tangmai the river turned south into a tribal area that remained almost unexplored. It is only accessible by foot trails that follow the river down through deep gorges. Most Tibetans do not know how to live in this kind of environment. They do not know how to survive the heat or how to treat tropical diseases with Tibetan medicine. I made a mental note and left the gorges for another trip. I turned west and started up one of the last passes that separated me from Lhasa.

The town of Dongzhou captured my interest. It is positioned between the jungle of Tangmai and the predominately high altitude Tibetan Plateau. The people of this town wear a style of dress that I had never witnessed before in Tibet. It consisted of a heavy brown wool poncho and an elf-like hat made of brown wool with a band of gold brocade around the edge. By Tibetan standards a luxury hotel operated in town. Fortunately, I got a room with clean sheets to myself. Most Chinese and Tibetan hotel rooms have four to six beds crammed into a single room with cold carpetless concrete floors and maybe a single window. Tibetans and Chinese never travel alone. It is normally the luck of the draw as to who else you share a hotel room with. The notion that Americans have of privacy does not really exist in China or most other parts of Asia. Being a foreigner, I would get a room to myself a fair amount of the time. There is still a practice of segregation when it comes to foreigners in this land.

After a hearty dinner, I returned to my room to write and relax. I heard a knock at my door, I called and two young Tibetans in Western clothes came into my room. We talked for a bit. I learned that one of them worked at the TV station in Bayi, a big military town between Dongzhou and Lhasa. I did not realize it at first but the other one was the local police officer. He seemed like a decent guy so I started to ask him about the towns between Dongzhou and Lhasa. He told me that Bayi and Nyingchi would definitely be trouble spots for me. He warned me that the police there would certainly hassle me. When I asked him about Dongzhou he replied it was “closed to foreigners,” smiled, and then said that it was also “open a little.” When he asked to inspect my passport, I knew I could trust him. I showed it to him and explained all the different stamps from countries in South America, Central America and other parts of Asia.

Since Tangmai my days consisted of continual climbing. After a day and half of uphill, many more miles lay ahead. By sundown I found a spot on the edge of the road to set up camp. With few level places around other travelers had obviously camped at this location. I could see a few patches of snow just up ahead, I knew that this was one of the last places to stop before the top of the pass. I started into my normal evening routine. I found three big rocks on which to balance my large metal mug and lit a wood fire under it to get the water boiling. I started to cook one of my standard dinners of ramen noodles with dried fish. Like most every day, I was starved, my belly ached for food. I could not wait to eat. In my hurry to get the food ready, I hit one of the rocks and spilled most of my dinner into the fire. Using my bandanna to protect my hand I recovered a good part of the dinner from the hot coals of the fire, but it still left me hungry. Just as I started to fall asleep, two Tibetan men and three mules decided that my camp was also a suitable place to spend the night. All of their mules carried heavy loads of goods from Bayi. Without a doubt they had come from the other side of the pass. I was not in a good mood and I just wanted to get to sleep. I did not want these guys poking around all my stuff. I felt tired and hungry.

I think they sensed my state of mind to some degree and started doing their own thing. The father found a few smoldering coals left from my fire and quickly rekindled a flame. Starting a fire at 13,000 feet [3963 meters] is never an easy job. At such a high altitude the air has little oxygen to keep a flame going, you have to almost continually blow on the coals for it to burn well. Meanwhile, the son collected more firewood and unpacked the mules so that they could freely graze during the night. When Tibetans travel usually the only thing they actually cook on the fire is a large pot of tea. The tea is then drunk and also used to mix with tsampa, toasted barley flour, to make a dough-like mixture that is eaten. Tsampa makes up one of the main staples of the Tibetan diet along with yak meat. Once their pot of tea started to boil, they called and asked if I wanted anything to eat. I crawled out of my sleeping bag, grabbed my thermarest mat and sat down by the warm fire. They instantly started to fill my cup with tea and gave me a couple of handfuls of tsampa. We exchanged few words, they spoke almost no Chinese and I had difficulties understanding their Tibetan, but as I sat around the fire with these men I felt I became part of an ancient circle that has gone on for thousands of years. These guys did not know me or probably anyone even from my country, but they went out of their way to make sure that I had hot tea to drink and food to eat. As I sat at the edge of the glowing fire and looked into their eyes I knew why I struggled through so many hardships on this trip, I knew that all the trials were worth it.

Later that night a cold young Tibetan boy with soaking wet tennis shoes showed up with no pack and no food. He also had just crossed the pass, walking through icy streams and snow fields. He was trying to get down to the warmer valley as fast as he could. The young boy did not have any warm clothes to wear but when he spotted the fire, he knew that he could get warmed up. The other men gave the boy some tea and tsampa and then went to sleep under the stars. The boy kept the fire going the entire night, curling up as close as he could get to the warming flames and coals. I knew that his back side would be freezing as his front baked from the heat of the flames.

Lhasa got closer day by day. I knew that I would arrive within a week’s time. Before I had left on this trip, so many people had told me that the journey would be impossible. Chinese friends thought that the trip would be extremely difficult, and when I said that I wanted to make the journey on a mountain bike they laughed. During a year and a half of research I only found one other documented case of someone cycling this entire route. When I started on the ride I could only focus on the section that lay immediately before me. To think about the trip in its’ entirety overwhelmed me. I had mentally divided the trip into a few different parts. While en route people would ask me where I was headed, I would say that I was going to Lhasa, and then they would ask where I was going after Lhasa, I would always answer, “Well, if I’m still alive and my bike is still functioning, then I am going to ride on to Mt. Kailash, or Kashgar.” By the time two weeks of this journey had passed, I knew that if I were turned back, it still would have been worth it.

The only big obstacles that stood between me and the delicious food at Tashi’s Restaurant in Lhasa were the towns of Bayi and Nyingchi. These towns were commonly known to be the worst places for police in all of Eastern Tibet. In 1992, two friends of mine tried to travel from Lhasa through Eastern Tibet to Chengdu, in Sichuan province. The police in Bayi apprehended them twice and sent them back to Lhasa after the second incident. I knew that my only chance would lie in traveling through both towns during the night. By the time I descended from the 14,500-foot [4420 meter] pass before Nyingchi, early evening had set in. As the road snaked its way down the mountain side I could see some of the buildings below me. I waited by the side of the road for the sun to start setting.

From my previous travels in Tibet and the helpful hints of other long-time Tibet travelers, I have developed a few rules of how to travel in this harsh land. The first is never go drinking with Khampa men, this is an easy one for me because I almost never drink. Next, always treat Khampa men with respect. They often have big egos, but given a bit of respect they have always gone out of their way to look after me. The last rule is: when the sun starts to set, know where you are going to sleep, and do not move around at night. In most towns packs of wild dogs roam the streets at night, only a few people travel around late at night and they are usually not the sort that you want to meet under the cover of darkness.

The problem with moving through town at night is that I have to break my own rules. The only reason that I could possibly sneak past the checkpoints during nighttime is because everyone else knows that they also should not be out moving around once darkness had settled in. Wild dogs and thieves patrol the streets, and if you are a solitary Chinese soldier there are Khampas who will slit your throat.

I came down the hill and rolled rapidly through Nyingchi. After just three blocks, I had already cycled passed town. Once I left town, the next problem was Bayi, which lay more than ten miles away. I had to ride the next ten miles in the dark, to pass through Bayi before daylight. At first that did not sound too bad, but the road turned into a surface of fist-size gravel that was a literal pain in the butt to ride on. I rigged my flashlight up to my hat so that at least I could see something of what lay ahead. The bumpy ride jarred me enough to cause the flashlight to fall out of my hat every few minutes. As I rode past some houses I would hear their dogs start to charge toward me. I would reach down and grab a handful of rocks to throw into the darkness. Whenever I saw the headlights of a vehicle coming up from behind, I pushed my bike off the side of the road into a ditch or behind a few bushes. I feared that if someone saw me on the road that they would report me to the police stationed at the next checkpoint ahead in Bayi.

I rode on. My butt hurt from the pounding of the gravel. I had no choice but to continue riding in the dark. Finally I came around a bend in the road where I could see the lights of Bayi glowing on the dark horizon. I knew just another few miles of riding would put me at the edge of town. On all of these bike rides past checkpoints I would have to mentally prepare myself to just ride. To keep riding unless someone physically stopped me. Still a couple of soldiers wandered around, most were a bit drunk and not interested in some crazy foreigner. I passed a couple of military compounds, a few blocks of restaurants, a fuel depot, and finally I saw the red turnpike and guard station in the bright floodlights, just ahead. It looked like the guards had called it an early night and retired for the evening. I quickly pushed my bike under the metal turnpike and kept moving. I peddled out past the edge of town and got a few hours of sleep behind a gravel pile off the side of the road.

I had moved closer to the big city, Lhasa. In my first hour on the road I saw more trucks than I would normally see in an entire day. Eastern Tibet has some of the largest stands of old growth timber in the People’s Republic of China. For the next week, I watched the huge three-foot-diameter [1 meter diameter] trees piled high in the backs of Chinese trucks move past me on the road. Regular bus service carried passengers between Bayi and Lhasa. I knew that I was getting close now. The last buses I had seen were back in Dali, almost 900 miles behind me.

The road continued on with the same bone-jarring gravel surface. The days of endless racquetball-size gravel wore hard on my tires, some of the tread on the sides started to peal off exposing the fibers that make up the tire. I did not carry any extra tires with me. After I had left the USA, I had a friend mail a new bike tire to Lhasa, along with a few other supplies. I just hoped that my tires would hold out for another 200 miles. The gravel required riding in one of my lowest gears. Normally I would only have to use those gears climbing a steep hill, but on that stretch of road I moved painfully slow. With only a couple days separating me from Lhasa, two vehicles full of Westerners passed me on the road. None of the passengers even smiled or waved. It was as if I did not even exist. I rode for a few days and never talked to another person, in any language.

A long slow climb took me up the last mountain pass before Lhasa. I climbed out of the temperate forest of Eastern Tibet and into a cold high altitude desert valley that looked and felt like the Chang Tang of Western Tibet. I could see no nomads on the horizon, the entire valley was devoid of inhabitants. The Khampas of Eastern Tibet do not like to live in such high desolate places. With fifteen more miles to climb to the top of the pass I stopped for the evening. The valley felt completely different from the rest of Eastern Tibet. It had the massive size and space of Western Tibet. Small purple flowers grew around my tent offsetting the harshness of this place.

I had read so many travelers’ accounts of trips to Lhasa. They always talked about the golden roof of the Potala Palace being the first thing that one sees of Lhasa. When I looked to the far end of the Tsangpo valley and saw the shining glimmering light of the golden roof of the Potala Palace, I knew that I had made it. I knew that all the suffering was worth it. I hit the paved road with a new-found energy. My bike computer reported that I cruised along at 20 mph [33 kph]. The kilometer stones on the side of the road flew past me at a new found rate.

Many Western people have some kind of almost mythical image of Tibet and the entire Himalayan region. Part of that image is the massive Potala Palace, the former winter residence of the Dalai Lama. Up until this century it had been the largest building in the world. During my visit to Lhasa in the fall of 1992, I found that the Potala was impressive from the outside but the inside seemed dead. The Chinese government had turned it into a museum. The Jokhang Temple had become the real heart of Lhasa.

Thousands of multicolored prayer flags cover the metal bridge across the Tsangpo River. I rode across in a daze of disbelief that I had made it to Lhasa. Only five weeks before I had begun this cycling trip. Once I crossed the bridge I headed straight for the Jokhang Temple, the mystical jewel of Lhasa. Wow! City traffic! I weaved my way in and out of donkey carts and motorcycles, stopped at the traffic lights, and a kind of happiness that I have never really understood filled me. There is something about Lhasa that just makes me happy, happy to be there, happy to just walk down the street and through the markets, and make a kora around the Jokhang. I rode up to the Barkor, the large plaza in front of the Jokhang Temple, and dismounted my bike. I later learned that when Tibetan pilgrims come to Lhasa the Jokhang is the first place that they visit. Just like most every other sacred place in Tibet it is standard practice to walk around the object or place in a clockwise direction or circumambulation. I walked my bike through the crowds and around the Jokhang making three koras or circuits.

The mandala concept is one that reappears often throughout Tibet Buddhism. A mandala is a circular map of the cosmos. A distilled representation of the universe. The mandala has a defined center that is marked by a central structure. This structure has four openings, one toward each of the cardinal directions, north, south, east and west. A outer boundary area surrounds the main central structure. The Milky Way galaxy, and solar system and the Jokhang Temple each represents unique versions of a mandala. Buddhist pilgrims use the action of the kora, traveling the circle that makes up the center of the mandala, to both calm and center their mind. Speaking a mantra at the same time helps to focus the mind and keep it clear of distraction. Both of these actions help to create the proper mental conditions needed to contemplate the true nature of reality. As I walked the koras around the Jokhang I took a little time to reflect on my experiences of the past few weeks and to rejoice in my arrival in Lhasa.

In all of Tibet, Lhasa offered the most when it came to material comforts and I knew that I could use a little physical comfort. I made the three block ride over to the Yak Hotel only to find that no one would help me. It seemed like the Tibetan staff there almost ignored me. When I saw myself in the reflection of the window, I knew why. Since I did not carry a mirror with me, I had not seen my face in weeks. By the time I reached Lhasa, road dirt and sweat covered me and my clothing. I was starting to look almost as filthy as some of the Tibetan nomads. I got back on my bike and rode down the street to the slightly lower class backpacker hotel, the Banok Shol. When I reached the Banok Shol, the Tibetan women there greeted me with big smiles, and pointed out that they had hot showers.

I spent a few days indulging in the luxuries of Lhasa. I would get up and go to Tashi’s Restaurant for some morning yogurt and oatmeal. After I ran a few errands and checked my mail at the post office, I would spend some time just hanging out talking to other travelers. By late afternoon it was time to start thinking about my dinner plans. My days had an obvious theme, eating and relaxing. I enjoyed the life of a true vacation.

There is a certain magic about being in Lhasa. At the center of this mystical town lives the Jokhang Temple, the magnet that draws prostrating pilgrims from thousands of miles away. The town consists of a strange mix of pilgrims, business people, and the worst of the Chinese police. When you stand in front of the Jokhang, you look out into a mass of pilgrims, undercover police, and vendors selling everything from prayer flags to Coca-Cola. When you glance up to check out the tops of the surrounding buildings, the rooftop surveillance video cameras watch your every move. The police are everywhere. Once, I saw three Tibetans make a small demonstration against the government. Within seconds, half a dozen undercover agents surrounded them. A few minutes later, a green Beijing jeep sped onto the plaza. The police forcibly shoved the demonstrators into the vehicle and carried them off to the police station, where an uncertain fate surely awaited them. At the same time, two Americans had been taking pictures of the Jokhang on the opposite side of the plaza. The police forced my American friends into a jeep and took them down to the police station to make sure that they did not possess any photos of the demonstration that had transpired moments before. My friends were oblivious to the demonstration and a bit perplexed by the police’s concern with what they had photographed. The police are extremely careful about implicating photos getting out to the Western press. Almost every Tibetan whom I met had served time in jail at some point in time, or their father or brother had been in jail or killed.

The pull of the 1300-year-old Jokhang Temple is one of the main attractions that brought me back to Lhasa. Like the Tibetan pilgrims who prostrate themselves for hundreds of miles and weeks on end to arrive at the Jokhang, I was also strongly drawn to this central hub of Lhasa. Most afternoons and evenings I would spend some time in or around the area of the Jokhang. In the front there is an area continually filled with pilgrims, largely consisting of older Tibetan women. For a majority of the daylight hours, these pilgrims perform prostrations by holding their palms together and raising them above their heads, lowering their hands down to their head and on down to their chest. They then kneel down on the stones and place their hands out in front and bow down to touch their forehead to the earth. The repeated motion of pilgrims who have prostrated on this spot for hundreds of years has worn the paving stones smooth. I walked past the pilgrims and into the tree-trunk size columns that support the massive beams holding up the roof. Waist-high on the wooden columns are shiny indentations worn away by the thousands of pilgrims that have rubbed their hands on the tree trunks. Between the first sets of columns resides a prayer wheel the size of a Volkswagen Bug that is filled with millions of written prayers. I grabbed the brass rail attached to the prayer wheel to help spin the oversized cylinder in a clockwise direction and release more prayers into the world. Prayer wheels represent yet one more Tibetan Buddhist tool for transforming the mind, first by calming and focusing the mind and then by planting the seed of the object of contemplation.

Once through the main gate you enter the central courtyard of the Jokhang. A group of five or six Tibetan men worked away on restoration of the two-and-a-half-foot-wide [0.80 meter wide] wooden columns. They all worked with hand tools, chisels, planes and an assortment of other old-style wood-working tools. When I stopped to chat with the workers it became apparent that they were all extremely grateful to have such a fantastic job. They knew that the work was difficult but to be able to help create some of the new wood carving for the Jokhang made for a enormous privilege and honor.

Surrounding the main courtyard is a maze of dimly lit rooms and halls that contain a large number of the remaining treasures of Tibet. An unending line of pilgrims flow in and out of these small dark rooms whenever the Jokhang remains open. The pilgrims carry hand-held prayer wheels and prayer beads as they walk though the labyrinth of halls quietly repeating the ever present mantra “Om Mani Padme Hum.” Over the course of dozens of visits I started to become familiar with just a few of the many rooms that contain wonderful paintings and statues. Bolted into the door frame of each of these rooms hangs a medieval-looking chain mesh that remains locked at certain times to protect the rooms from thieves and treasure hunters. As I examined each of the rooms some of the older pilgrims would often help me to identify the statues and the paintings of various Buddhas and images of famous Tibetan Buddhist teachers illuminated by the burning butter lamps. During one of my visits I noticed an oil lamp burning on a table in the corner of the room. The top of a human skull formed a bowl that held the oil for the burning lamp. This reminder helped to keep all of the visitors mindful of their own mortality and of the true nature of our short time on this planet.

During a trip to India I learned this lesson in a way that would never be possible in the USA. On the banks of the sacred Ganges River in north India lies the city of Varinasi. For Hindus this is one of the most holy cities in India. Near the river’s edge descends a series of stone steps, called ghats, that lead down to the water. Every morning the ghats fill with Hindus who come to wash and bathe in the most holy of rivers, the Ganges. Alongside these bathers, vendors, and holy men are the burning ghats. From these places along the river’s edge the flames of cremation fires rise into the sky. A few months before, in Nepal, I witnessed my first cremation. I looked across the river at the burning corpses and had the luxury of a close friend who sat at my side to help explain and reflect on exactly what we watched. In Varinasi I stood alone just a couple yards from a burning corpse. I drew into my lungs the pungent smoke that poured off the body. One moment these particles were the physical death of someone whom I had never met and the next they were part of the force that kept me alive.

The Tibetan calendar is based on a twelve-month lunar calendar. The full moon is always the most auspicious day of the month always falling on the fifteenth day of the month. Out of all the months of the year, Saga Dawa represents one of the most special. It is a month to celebrate and reflect on the birth, death and enlightenment of the Buddha. I had the good fortune to be in Lhasa during the month of Saga Dawa. In the Western calendar Saga Dawa often falls in the month of April or May.

In a local restaurant, I heard about a festival at Tshurphu Gompa. Tshurphu is the home of the nine-year-old incarnation of the Karmapa. Alongside the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama, the Karmapa is one of the most powerful religious figures in Tibet. This festival was part of the month of Saga Dawa. At 6 A.M. I found a minibus in the Barkor headed to Tshurphu. Tibetans going to the festival packed the bus. Once we got underway, a couple of young Tibetan guys started speaking to me in English. They were both children of Tibetan refugees and had been born in Nepal. For the first times in their lives they traveled the land of their ancestors. Growing up they heard countless stories about Tibet but they had never before been able to actually see the land of their parents and grandparents. Sonam had spent some time in Singapore, where he learned a bit of Chinese, a useful skill for dealing with the Chinese officials and police.

Two years before, this Tibetan child was recognized as the incarnation of the Karmapa, the leader of one of the four sects of Tibetan Buddhism. The search for this young boy had lasted for eight years. The Chinese government handled the entire situation fairly suspiciously. They allowed the initiation ceremony to take place but Chinese government officials forbid the Karmapa to leave Tshurphu Gompa without permission. A few Europeans lived at Tshurphu, each spending a couple hours during the day teaching the young lama about the 'West' and the English language.

The small bus made its way over the rocky road. Every now and then a few of the passengers would disembark to move large rocks off the road. Fresh snow blanketed the hills above the monastery, adding to the beauty of the valley. A complex of old Tibetan buildings formed the monastery. The bus dropped us just in front of the gompa or monastery, I hefted my pack up on to my shoulder and started the short walk up to the main courtyard. I strolled past a Chinese solider holding an assault rifle. The soldier did not seem a part of the whole picture around me. I was at a Buddhist religious festival, the need for armed troops eluded me.